When I was a teenager in a small northern British town, it was my ambition to become a French philosopher when I grew up, and spend my days reading and writing in an atmospheric Paris cafe. My old friend Daniel Cohen, an economics prof at the Ecole Normale Superieure, has achieved this ambition on my behalf. His new book [amazon_link id=”026201730X” target=”_blank” ]The Prosperity of Vice: A Worried View of Economics[/amazon_link] (out next month) covers the territory that interests me – historical trends, the changing deep structure of the economy, the multiple crises or points of inflection facing our societies – and does so in an elegantly Gallic way. This is a slim 200 page volume, not a three volume tome. Once on a business trip in Paris during an election campaign, I caught a late night discussion programme on TV. The guests had evidently been given a fine meal and plenty of wine in the studio, then the cameras quietly turned on. This book reminded me of the character of that discussion: rather abstract and high-fallutin’, but immensely entertaining too. You have to like that style to enjoy the book: I very much do like it.

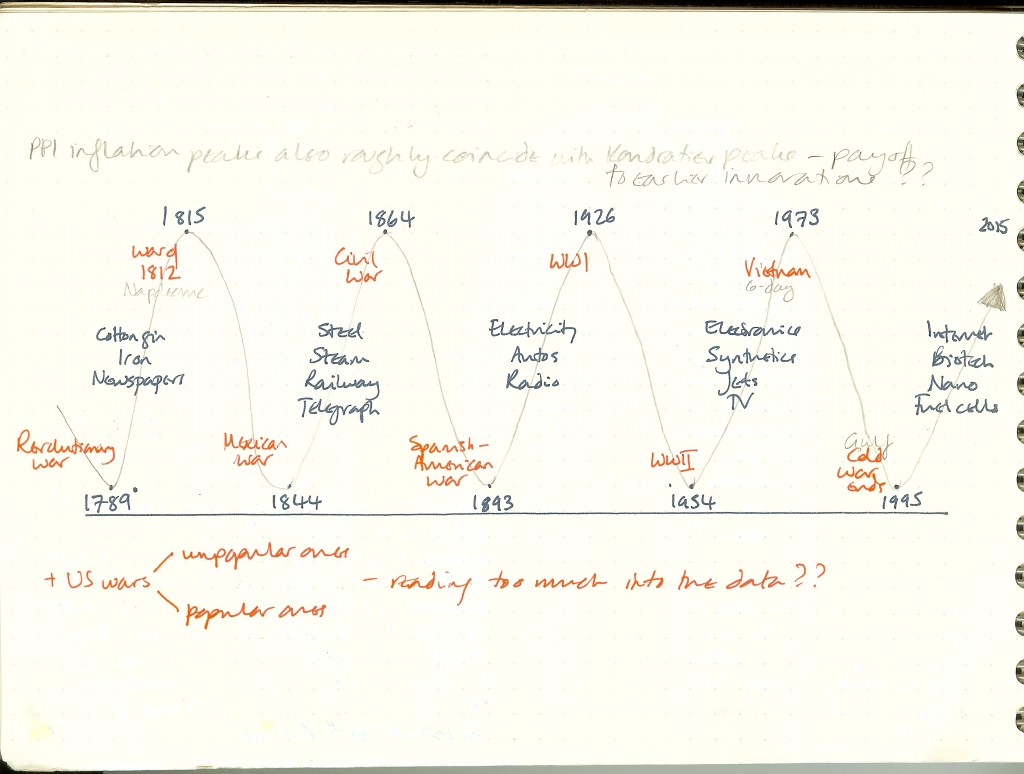

The bulk of the book addresses global economic history, looking at the different accounts of what has driven economic growth and the escape from the Malthusian trap: culture, the competition of ideas, institutions, resources, trade. The classics of economic history are all referred to, both French and English (I am needless to say not familiar with the former group). Daniel includes a discussion of Kondratiev cycles, which [amazon_link id=”1843763311″ target=”_blank” ]Carlotta Perez[/amazon_link] has recently popularised again in the Anglo-sphere. Here is a diagram from one of my old notebooks (2002) which sums it up:

The Kondratiev long wave view

The worry to which Daniel’s subtitle refers is that the limit of post-Malthusian growth has been reached because of both environmental and social constraints. The latter include the emerging generational conflict due to demographic change and apparently intractable inequality. (He does also worry about the supposed breakdown between growth and happiness. Regular readers of this blog will know about my happiness-scepticism, so I’ll draw a polite veil over this section of the book.)

The book does end on a slightly more cheerful note, discussing the importance of ideas and images – “the other theatre of globalization”. He even refers to the ‘weightless’ economy (although alas not citing my 1996 book The Weightless World (pdf).). This may yet allow us to develop a new form of global society and new technologies to address the ecological crisis, he suggests. “At a time when it is tempting to wander around in the cyber-world, human kind should accomplish a cognitive task as immense as that realized during the Neolithic Revolution or the Industrial Revolution: to learn to live within the limits of a solitary planet.” (p188). But that’s not quite his last word – he concludes that there is huge uncertainty about whether we are up to the challenge.

So there is an melancholic mood in the end. If you find yourself in a reflective and philosophical mood one quiet Sunday afternoon, when it’s cold and grey outside, but cosy on the sofa with some Bach or Keith Jarrett or maybe the new Leonard Cohen album playing in the background, this is an ideal read.

[amazon_image id=”026201730X” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Prosperity of Vice: A Worried View of Economics[/amazon_image]