A few days ago, John Kay wrote a characteristically brilliant column about money, Money, like hat wearing, depends on convention, not laws. It was about the acceptance of Scottish bank notes – in Scotland, and in some places in London, but not elsewhere. He wrote:

“There is a widespread reluctance to accept that behaviour is governed by social norms rather than legal rules or abstract principles. I wear a tie today not because I want to, or because anyone requires me to, or because I think that it is right that I should do so, but because of a shared convention that I will. …

I tip in restaurants or cabs, but not post offices or doctor’s surgeries. Often there is some underlying reason for these practices, although I cannot think of one that applies to the habit of tie-wearing. But in any event it is custom, not reason, that leads me to do it. The Scottish pound is accepted where it is accepted, and not where it is not. There is really no more to it than that.”

As it happened, I was reading at the same time John Searle’s [amazon_link id=”0199576912″ target=”_blank” ]Making the Social World: The Structure of Human Civilization[/amazon_link], which is about exactly the same point.

[amazon_image id=”0199576912″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Making the Social World: The Structure of Human Civilization[/amazon_image]

Searle makes the even stronger claim that all human institutions are created and sustained in existence by “collective recognition”, which is dependent ultimately on communication. He sees all institutions as general examples of Austin’s “performative utterances”, which “make something the case by declaring it to be the case.” (p69)

There are many examples, of which money is one. So are political institutions and roles: the prime minister is the leader of the party that wins the most seats in a general election because we agreed that it is so. Another example I’ve been pondering is property: intellectual property is clearly an abstraction dependent on social convention, but physical property is too. When I buy a meal in a restaurant, convention tells me I have bought the food, and can take home what I don’t finish, but I can’t tuck the plate into my bag to take away when I’m done.

There’s an even more interesting question arising from this issue of performativity in the economy: what is the effect of the new forms and scope of communication on economic and political institutions? Intellectual property is on the front line of the struggle between old institutions and new ones shaped by the new technologies. Facebook and Twitter and the like offer completely new opportunities for performative declaration. Many other struggles will follow.

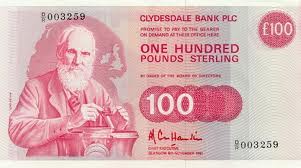

100 Scottish pounds

Fascinating area, and one of the key mechanisms not sufficiently studied in economics is just _how_ these conventions come into being, and what can make them stronger or weaker.

I think your picture caption attempts a performativity that is beyond its power, though: technically that’s not “100 Scottish pounds” but “a Scottish 100 pounds”. Pace Alex Salmond, there is as yet no “Scottish pound”.

You are right of course!