The Office for National Statistics has just published a really interesting new paper estimating the size of the UK’s capital stock. The figure (£17.12 trillion in 2010) depends on certain assumptions – more on those below – but one key point is the general scale. That’s two and a half times the size of the country’s physical capital stock. Even varying the assumptions generates estimates larger than the value of all the factories, machines, vehicles etc.

No wonder both the theory and evidence (see for example Barro and Salai-i-Martin in [amazon_link id=”0262025531″ target=”_blank” ]Economic Growth[/amazon_link]) find human capital to be vital for economic growth. Although the importance of ‘education, education, education’ has become a commonplace, its role in the productive capacity of the economy is given much greater weight when you appreciate just how significant in scale the human capital stock is.

[amazon_image id=”0262025531″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Economic Growth[/amazon_image]

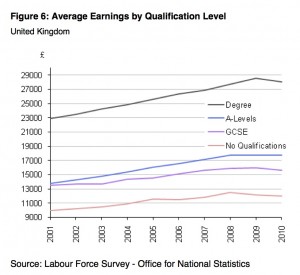

Interestingly, the paper estimates that the UK’s stock of human capital declined in 2010 due to the downturn. This is an effect of recession that has to be factored into any view about the productive capacity of the economy when it eventually recovers. The chart shows that the dip can be attributed mainly to lower real earnings for the highly qualified. If those made redundant or remaining unemployed can be re-employed quickly in equally good jobs, there’s no lasting damage. But otherwise recession erodes the value of these human assets.

Developing and publishing annual estimates for the human capital stock may even provide a useful corrective to the snap reactions one often gets after a natural disaster, which often present a nasty paradox of the destruction boosting economic growth because of the rebuilding required. But disaster is disaster, and the loss of lives is not only a terrible human cost but also the loss of a vital asset whose importance greatly outweighs the value of the buildings and roads.

The ONS estimates are based on the estimated lifetime earnings of the workforce, the outcome of investment in human capital through education and training. This is one of three possible approaches to measurement. One alternative measures expenditure on education and training, and the other measures educational attainment. Each has advantages and drawbacks. The main drawback of the one chosen here is that it assumes people are actually paid the value of their (marginal) contribution to economic output, and there are all kinds of reasons why that might not be true. Other assumptions concern the discount rate to apply to lifetime earnings, and labour productivity growth – the sensitivity analysis shows these do make quite a difference. Other shortcomings are that the estimates don’t take account of externalities which clearly exist, for example when the presence of other skilled people makes my own skill more valuable because employers will offer better jobs, nor of social effects of investment in human capital. The benefits of a high trust, civilised society are in a league of their own, compared to the mere economic benefits.

Nevertheless, it is very important that the ONS has undertaken this exercise, and I hope it will be updated annually. In [amazon_link id=”0691145180″ target=”_blank” ]The Economics of Enough[/amazon_link] I argue for the importance of measuring the economy’s comprehensive wealth, including human capital, to take proper account of the effect of today’s decisions on the future capacity of the economy. Without an estimate of all our assets, we simply can’t know whether the economy is on a sustainable path.

[amazon_image id=”0691145180″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Economics of Enough: How to Run the Economy as If the Future Matters[/amazon_image]