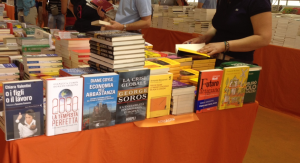

At the fabulous Trento Festival of Economics I picked up a copy of Dani Rodrik’s talk from last year, which sent me to his terrific book, [amazon_link id=”0199603332″ target=”_blank” ]The Globalization Paradox[/amazon_link]. The challenge he sets out is that we have a combination of economic globalization and national politics, and it’s difficult to see a way out of the mismatch because political legitimacy is created at the level of the nation state. To call for ‘global governance’ is unrealistic – and clearly all the more so now the Eurozone is wholly unable to deliver zone-wide political responses to the economic crisis. The global institutions that we have, like the WTO, lack legitimacy.

[amazon_image id=”0199603332″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Globalization Paradox: Why Global Markets, States, and Democracy Can’t Coexist[/amazon_image]

So Rodrik draws three conclusions:

“Markets need to be deeply embedded in systems of governance to work well.”

“These institutions of governance…. are organized largely within nation states and they are likely to remain so.”

There is no single way to design institutions and governance. “The institutional designs that underpin market economies will differ according to the democratic preferences of different jurisdictions.”

This makes it pretty scary that the economy has become as globalized as it is in a world of firmly national politics that seem to be getting more nationalistic by the day. Richard Baldwin’s recent work on the ‘two unbundlings’ – the separation of production from consumption and then of steps in the production chain from each other – indicates that reversing globalization would be catastrophic economically. But how are world markets to be governed when these supply chains link separate nation state institutional frameworks?

I don’t have an answer but do think one path forward will involve using the structure of supply chains themselves to govern economic activity. There are many industries where standards bodies and trade bodies are reasonably effective, where export credits work very well, where large companies at the head of the supply chain provide leadership. These are not state bodies, but they are collective institutions – maybe part of the answer to Rodrik’s paradox will lie in expanding the domain of these institutions and not expecting the state to solve everything. Especially given the dysfunctionality of politics and lack of trust in politicians everywhere.

Fabulous Trento