There is an epidemic of Olympics-related cheerfulness in the UK, for obvious reasons. The Post Office is painting a post box gold for every Team GB gold medal, London is full of cheerful (mainly non-athletic) people in athletic clothes, and the vast majority of people are (literally) watching the sport and chatting about it. There has been quite a lot of discussion about whether the Olympics will be positive for the economy or not; the weight of opinion is leaning towards not, because normal tourist and retail spending is significantly down on normal levels, and because there is a lot of surreptitious Olympics-watching going on at work.

I read this morning a recent paper by Roger Farmer of UCLA, The Evolution of Endogenous Business Cycles, and it set me wondering if the psychology of Olympic success might actually have a lasting positive effect on the economy. The paper describes the evolution of the way business cycles have been modelled in modern economics. In the late 1970s/early 1980s the Real Business Cycle models dressed old classical, equilibrium models of cycles driven by exogenous supply shocks in new mathematical costume. The economy doesn’t behave like this, however, so nominal wage rigidities were added to give us the workhorse Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium models, enriched by a number of complications over time. Farmer writes that a DSGE model, “Loaded up with enough frictions and multiple shocks, does a credible job of replicating the dynamics of post-war U.S. business cycles.”

In the mid-90s, Farmer and his co-authors introduced “sunspot” dynamics, self-fulfilling changes in expectations that could account for business cycle departures from full employment that would last for a time before the economy returns to normal. However, the disequilibrium could not last all that long or have a high welfare cost. In two recent books, [amazon_link id=”0195397916″ target=”_blank” ]How The Economy Works: Confidence, Crashes and Self-fulfilling Prophecies[/amazon_link] and [amazon_link id=”0195397908″ target=”_blank” ]Expectations, Employment and Prices[/amazon_link], Farmer introduces a labour market that cannot readily match workers to jobs because of the costs of searching. The latest version of these endogenous business cycle models therefore features self-fulfilling dynamics and unemployment that persists and can be large scale. He presents a rigorous (‘micro-founded’) Keynesian model that seems to explain the post-crisis behaviour of the economy. Farmer points out that macroeconomic data demonstrate strong persistence over time, something many models gloss over by the way they filter the data, whereas his model describes it explicitly.

I find this very interesting (not least for the personal reason that in my 1985 PhD thesis I tried and very much failed to marry search and efficiency wage labour market models with Real Business Cycle thinking in a way that fit the data!) This paper is the most persuasive I’ve read on the continuing usefulness of technical micro-founded DSGE-type models – and after all, central banks and governments continue to need macro models and forecasts. However, the absence of financial institutions – and the specific characteristics of banks and financial markets that explain why normal transmission mechanisms are failing – still seems to me a glaring gap, given the experience of the crisis. I’m also interested in the contribution network/epidemic models can have to understanding changes in expectations and behaviour.

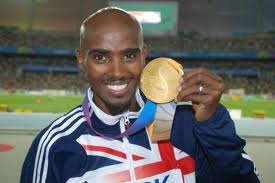

But the important role of self-fulfilling changes in expectations – another Keynesian insight – did also strike me as I read the paper. Hence, perhaps, a little ray of hope shed in the UK by our Gold medals at the Olympics.

An economic as well as athletic triumph?