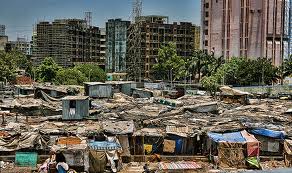

Katherine Boo’s [amazon_link id=”1846274494″ target=”_blank” ]Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Slum[/amazon_link] is a wonderful read. It recounts a series of dramatic events that occur in Annawadi, a slum next to Mumbai Airport, where she spent months meeting residents and observing their lives. Like all good reportage, it gives the reader a vivid impression of place, and Boo has a novelist’s ability to convey character. In fact, my one complaint about the book is that she uses the novelistic device of voicing the characters’ inner thoughts – for me, this undermined the authenticity of the detailed reporting of the physical conditions, the work, the danger, the smell and dirt and noise, and so forth. On the other hand, the focus on character makes it a very enjoyable book.

[amazon_image id=”1846274494″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Slum[/amazon_image]

The business at the centre of the tale is recycling rubbish, which also featured in the episode of Welcome to India I watched last week. I won’t spoil it by giving away the ‘plot’. However, I was particularly struck by the absolutely central role monetary transactions play in everyday life. It is a commonplace to say corruption helps trap countries like India in poverty. I suddenly realised that there is a vicious circle, because poverty also traps people in corruption. The sort of favours and kindnesses that people in my society wouldn’t dream of demanding payment for all require handing over cash in the slum. Money is so short that nobody will do something for nothing. Besides, there is a chain of transactions to sustain. Policemen are paid so little that they demand bribes, a slum entrepreneur needing to pay the bribe to keep the police from closing her business as it lacks a permit therefore has to ask for cash to help out a neighbour, and so on.

Anyway, it was thought-provoking to realise how monetised all these relationships were in the light of having read recently Michael Sandel’s [amazon_link id=”184614471X” target=”_blank” ]What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets[/amazon_link]. Behind the Beautiful Forevers makes it brutally clear that these moral limits are income-contingent: a very poor community has far less scope for scruples than a wealthy western one with a social safety net.I think Sandel’s widely cited example of the immorality of paying people to hold your place in a queue would be met with simple bemusement in Annawadi.

Worth reading alongside this book: Sukhetu Mehta’s [amazon_link id=”0747259690″ target=”_blank” ]Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found[/amazon_link]; [amazon_link id=”0199794642″ target=”_blank” ]Working Hard, Working Poor[/amazon_link] by Gary Fields; and [amazon_link id=”0691148198″ target=”_blank” ]Portfolios of the Poor[/amazon_link], which uses diaries to record how people with almost no money use what they have. There are some good background features on Katherine Boo like this one in The Daily Telegraph and this New Yorker video.

Annawadi

I have spent some time in India and I think you’re highlighting an important point about how monetised relationships are in the slum. I think I’d generalise out and up (since Nesta have just produced their report on innovation in Britain) that entrepreneurialism of all kinds is affected by the level of monetisation – which in turn is related to the level of general wealth. So many startup stories seem to hinge on some element of if not gift then at least a very loose loan – “you can use this office and pay us back later” or “we’ll spot you this service for now” – but it’s all dependent on various kinds of general wealth.

Yes, I think you’re probably right – entrepreneurship as making a profit from something not previously done for profit.

Pingback: Innovation – in English | The Enlightened Economist

Pingback: Facts and fictions | The Enlightened Economist