Somebody reminded me recently that a review of my very first book, [amazon_link id=”1900961113″ target=”_blank” ]The Weightless World [/amazon_link](pdf) (1997) had accused me of committing some faults of techno-utopian naivety in proposing how governments and all the rest of us might respond to the structural changes being driven by information technology and globalisation. It prompted me to be self-indulgent and have a look at the book for the first time in ages. (Here is a free pdf file if you want to look for yourself.)

[amazon_image id=”1900961113″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Weightless World: Thriving in the Age of Insecurity[/amazon_image]

My verdict? That over-optimism on some issues is a fair charge. Like many other economists, I underestimated or ignored the changing character of the financial and corporate sector, the breakdown among the corporate elite of the social norms that sustain capitalism, and the increasing rent-seeking activity as the rich elite stacked regulations and tax systems ever more in their own favour.

On the other hand, I think it was pretty good going in 1996-97 to identify the way the technological changes would dramatically affect business, value chains and the demand for labour, and to say both the structure or delivery of government and the specific policies of governments needed to change in order to equip citizens for the new kinds of risk and uncertainty. I also think I was the first person to coin the description of ‘weightlessness’, inspired (if that’s the right word) by an Alan Greenspan speech.

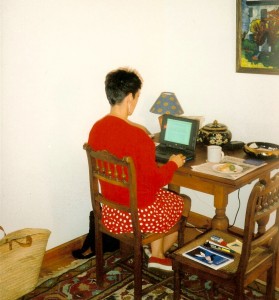

Me in 1996, writing The Weightless World