I’m pondering what to write about Erik Olin Wright’s [amazon_link id=”184467617X” target=”_blank” ]Envisioning Real Utopias[/amazon_link], for a debate in the New Year over at Crooked Timber. The book has a few examples of ‘real utopias’ – the Mondragon co-operative, Wikipedia – but only a few. It set me pondering about putting utopianism into practice. Of course, the internal contradiction of ‘real utopias’ is intentional. Thomas More knew no such societies were possible when he wrote the original [amazon_link id=”0140449108″ target=”_blank” ]Utopia[/amazon_link]. As in so many socially progressive movements, the Victorians were the real pioneers. Robert Owen is one of my favourites, manager of a Manchester mill and a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society before going on to turn New Lanark into a ‘real utopia’.

I’ve not read much of Owen’s work, and that a long time ago, but found certainly in my youth found it hard to disagree with any sentiment he expressed in [amazon_link id=”0140433481″ target=”_blank” ]The Social System[/amazon_link] (1826): “To train and educate the rising generation will at all times be the first object of society, to which every other will be subordinate”. And in New Lanark he put into practice his view about the importance of early intervention, more than a century and a half before this truth was rediscovered in modern policy: “The Institution has been devised to afford the means of receiving your children at an early age, almost as soon as they can walk. By this means many of you, mothers and families, will be able to earn a better maintenance or support for your children; you will have less care and anxiety about them, while the children will be prevented from acquiring any bad habits. and gradually prepared to learn the best”. (Address to the Inhabitants of New Lanark, 1816). New Lanark didn’t close as a working mill until 1968.

Although I can think of other utopias, imagined ones of early modern times and actual ones in Victorian times, existing modern ones are hard to find examples of. Any suggestions?

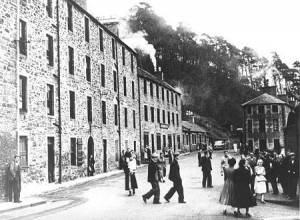

New Lanark in the 1950s, from http://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/lanark/newlanark/index.html

I’ve got his ‘A New View of Society’. I was something of an Owen fan when I was younger, too; him being a good Welshman and all. But after reading his own words, and what others have said about him I not sure I feel the same way these days.

There’s something about his paternalism that I found quite stifling. Unhealthy even. Reading about him, it became apparent that he wasn’t a saint blessed with good fortune by the Grace of God, but an entrepreneur and a human being, struggling and fallible like the rest of us.

I’ve mentioned it on your blog before but that New Heaven, New Earth by Burridge is in the same territory as ‘Utopias’. Owen was a Prophet creating a vision around Money; an archetype that is cross-cultural and timeless.

Paternalism is something best applied by oneself to others, rather than the other way round, clearly. But I like a bit of it in an employer – John Lewis, or the old M&S, leap to mind. In general, though, I’m in the pragmatism rather than the utopian idealism camp. I’d forgotten about Burrridge, thank you for the reminder.

It’s a good question, but aren’t so many political fashions of our time quintessentially utopian? The notion that markets self-regulate, for example, or top-down political structures (EU) can drag the people along behind them, both stem from idealism.

Thomas More coined the word quite carefully – utopia means ‘no place’; it not only doesn’t exist, he was saying, but it can’t: there’s something missing. What makes this so interesting to study is at what point idealism (which is admirable) turns into utopianism (which isn’t, there are considerable human costs). Some psychological or sociological factor has been overlooked, and becomes airbrushed out. Often it’s human agency.

May I suggest the place to find utopias today is on the internet? There can’t have been a greater invention for projecting utopian fantasies!

The free market ideal as a utopia – excellent point. Look how badly it was hijacked, too, as we survey the wreckage of the financial sector.

Your argument certainly accounts for why ‘Envisioning Real Utopias’ has so few actual examples of them, and one of those is Wikipedia. My other thought was that utopias might be possible on a small scale but not a large one – microcredit and local currencies could count as examples.