The social and economic aspects of new technologies have been my abiding interest for years, naturally from the perspective of my training as an economist.[amazon_link id=”0262018624″ target=”_blank” ] Robot Futures [/amazon_link]by Illah Reza Nourbakhsh has the same interest from the perspective of a Professor of Robotics, and director of the Community Robotics, Education, Technology and Empowerment Lab at Carnegie Mellon. It’s an eye-opening book (and a short, clearly written one).

[amazon_image id=”0262018624″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Robot Futures[/amazon_image]

There are two key messages I took from the book. First, we’ve already gone a long way towards weaving robots into everyday life without realising it. The advances in the physical manifestations of robots (which Prof Nourbakhsh divides into perception, cognition and action) will before long join up with recent innovations online, in the pooling of information including from social media. The issues we’re grappling with such as online privacy and identity will move off the screen onto the pavement. We might soon meet robots on the street who know everything about us. Already due to smartphones, he writes: “Nothing is transient because everything can be captured and shared. Expectations of privacy have to shift….. As robots decide automatically just what to record and publish, so our sense of internet identity will have to change. We humans will no longer be the only species that records events and publishes them online…. When you run into a well-connected robot, it will be unclear from first impressions whether the robot knows everything about your day….”

Or, to take another example, prosthetics and robotics are merging already; how far should that merger go? Science fiction ([amazon_link id=”0586057242″ target=”_blank” ]I, Robot[/amazon_link] and on) is stepping into life, and there are countless emotional, ethical and other issues.

The second message is about the economic and political issues, and is that unless there is a public debate about advances in robotics, their development will be commercial. As the book puts it, the early adopters are business and the military. Prof Nourbakhsh writes: “I have served on funding boards and I have seen technical content dwarf social impact in the eyes of nearly all the reviewers in the room. This needs to change; broader impact must become an authentic criterion for funding.” His lab specializes in socially focused robotics development, but I don’t imagine there are many others, or much social science thinking about the issues yet. There needs to be – it will be upon us soon.

The book has a useful summary of the state of robotics research, which has been uneven. Batteries/energy are still a big hurdle. It opened my eyes to the diversity of machines gathered under the term, including industrial robots, those innovative joints restoring movement to injured or disabled people, drones, household devices and so on. It touches on the ethics of how robots should be treated: “Never before have we had the chance to dehumanize socially agile non-humans. If this happens, then we face the odd technological side-effect that, as we dehumanize our relationships with robots, so we may incidentally dehumanize our relationships with people.”

In short, a lot of food for thought in 130 pages (albeit somewhat steeply priced).

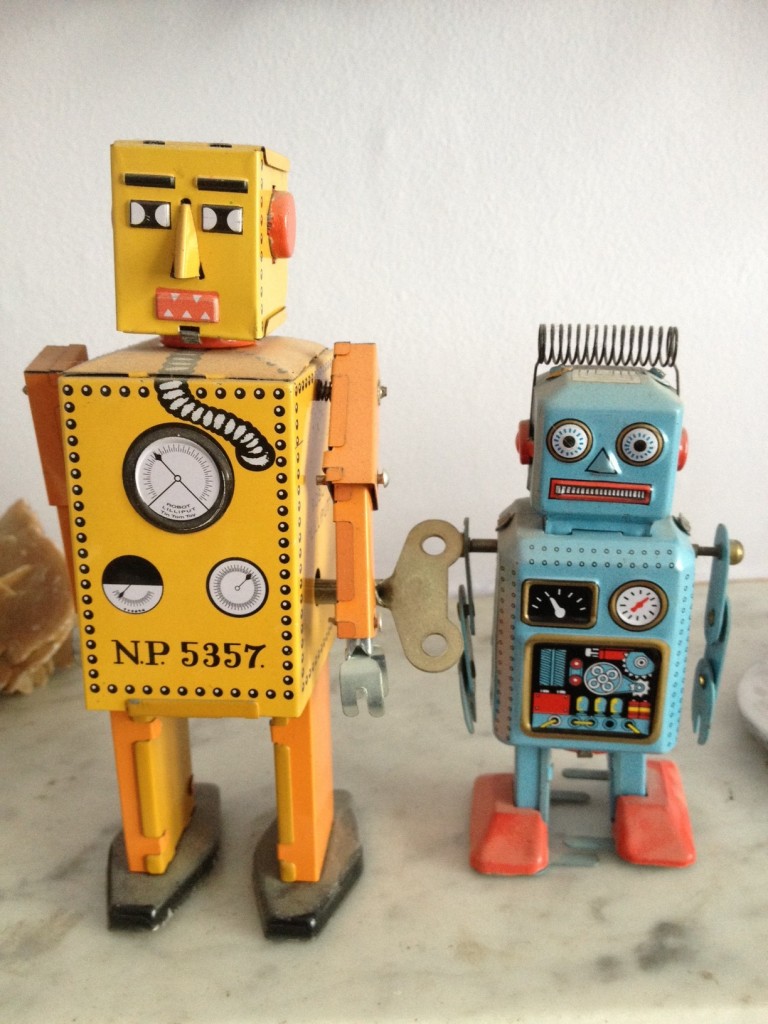

These robots are nice but dim…