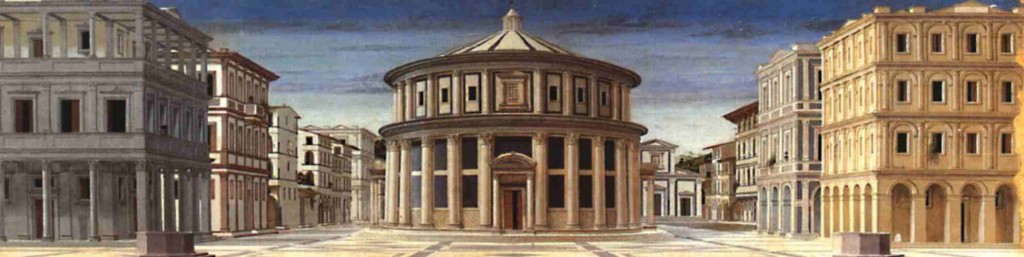

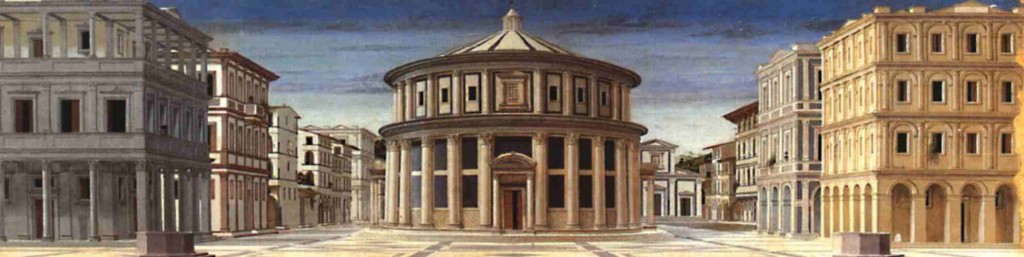

This summer we visited the wonderful gallery in the ducal palace in Urbino, where the painting that most absorbed me was Laurano’s Citta Ideale.

Citta Ideale

Of course it isn’t ideal – no people, no bustle. For any fan of Jane Jacobs’ [amazon_link id=”067974195X” target=”_blank” ]The Death and Life of Great American Cities[/amazon_link] or [amazon_link id=”0394729110″ target=”_blank” ]Cities and the Wealth of Nations[/amazon_link], it’s the anti-ideal.

Cities are clearly having a major renaissance, in debate if not in reality. Last year brought Ed Glaeser’s excellent [amazon_link id=”0330458078″ target=”_blank” ]Triumph of the City[/amazon_link]. Benjamin Barber has just published If [amazon_link id=”030016467X” target=”_blank” ]Mayors Ruled the World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities[/amazon_link], which I’ve not yet looked at. I’ve just been reading a very interesting analysis of the economics and politics of US cities, [amazon_link id=”081572151X” target=”_blank” ]The Metropolitan Revolution: How Cities and Metros are fixing our broken politics and fragile economy[/amazon_link] by Bruce Katz and Jennifer Bradley. The first part is descriptive, looking at four American urban areas and the ground-up initiatives under way to stimulate economic revival and involve citizens in urban and civic renewal. The four are New York, Denver, north eastern Ohio (Cleveland, Akron, Canton etc) and Houston. For a non-American it is simply interesting to learn what’s been happening, although the chasm between rich and poor areas is in my experience far greater in the US than anywhere in Europe (bad as it is in our cities too).

[amazon_image id=”081572151X” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Metropolitan Revolution (Brookings Focus Book)[/amazon_image]

The second part is analytical, drawing together some of the themes about the effectiveness of different approaches to economic development, in the context of big technical, demographic and cultural changes. Technology-driven innovation has clearly increased the value of the externalities that occur in densely-populated and well-connected cities – ideas and trade are the vital ingredients.

The recipe for combining them to achieve economic and cultural success is the subject of the final two chapters. They constitute a call to enhance the devolution of political power down to the city-region level (and of course American cities already have freedoms to act that British city leaders can only wistfully dream of), and to have the confidence to act with conviction in creating their own destiny. I particularly like Katz’s and Bradley’s emphasis on “the informal power to convene.” It’s what I think of as proper, old-fashioned politics, talking the people and getting them to line up in support of a common aim. The Ohio example is particularly interesting here, as the book describes its (partial) economic recovery as a matter of building networks of enterprise, investment and civic engagement. The details are specific to the US, but it seems obvious to me that the general principles apply here in the UK too.

The other new book to mention in this context is Bridget Rosewell’s Reinventing London, in our Perspectives series. Bridget is probably the most knowledgeable and authoritative commentator on the London economy, given her involvement over many years in developing its economic strategy. The book draws lessons about the post-financial crisis shape of London’s economy from the city’s past successful adaptations to profound structural changes. Its recommendations cover four areas: supporting service industries other than finance, making London a place people want to live especially by ensuring there is enough housing in pleasant areas, and investing urgently in infrastructure and also specifically connectivity – including deciding soon on new airport expansion, wherever the new runways are to be built.

[amazon_image id=”1907994149″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Reinventing London (Perspectives)[/amazon_image]

Needless to say, I strongly recommend it!

Is this the dawn of an era of powerful cities and weak nations – much like the age of city states half a millennium ago? It seems highly likely. More than half the world’s people live in urban areas now. Most economic activity consists of trade in ideas and people and goods and services between cities. Mayors are important figures, who for the most part feel less bound by the constricting conventions of national party politics. As ever, though, political and social institutions lag behind technological and economic trends, and in centralised polities like the UK urban renaissance would involve some big changes. Even London, with more powers than any other UK city, has only limited control over its own destiny, airport included. But if all these books are right about the inexorable trend towards city-driven economies, this will be an important debate.