[amazon_link id=”B0081H4KUA” target=”_blank” ]The Social Framework[/amazon_link] is the title of a short book by John Hicks published in 1942. It’s an introduction, for the general reader, to the then-new fangled concept of national income accounting – beautifully clearly written and very straightforward.

[amazon_image id=”B0081H4KUA” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Social Framework. An Introduction to Economics. Third Ed.[/amazon_image]

The book is upfront about the limitations of the exercise. For example, Hicks explains that it is progress if people work on average fewer hours to produce the same quantity of goods and services, even though the national income or output will not rise. Progress can be “deliberately taken out in the form of increased leisure.”

There is a very interesting passage concerning which part of government spending should be counted as national income – in short, the part used to purchase services people would otherwise buy for their own consumption. So police instead of hiring a bodyguard, education and healthcare rightly are included in the total. But – ideally – public spending incurred to facilitate the production of private goods and services should not be. Hicks writes that in principle the total should exclude policing that is a response to general crime (hiring a night watchman would be a cost of production), or military spending needed to fight an aggressor. Interest on national debt should be excluded too. Spending on roads should be included to the extent that travel is final consumption, excluded to the extent that it is an intermediate input into other consumption. This was of course all too hard so the whole of G is included in GDP.

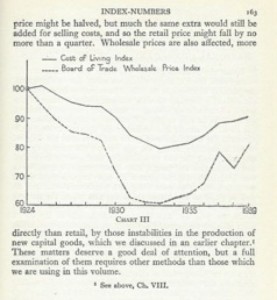

The chapters on price indices and the calculation of real national income are also full of caution, compared to modern usage of the figures. Hicks cautions against over-interpreting changes in real national income: “When there has been a great change in circumstances, as may sometimes happen even with years which are very close together…, any kind of comparison needs to be made with great circumspection. There is a nice chart to remind us what deflation really looks like:

Deflation

There are other interesting observations. For instance, that owners (shareholders) have no responsibility for the upkeep or state of the capital equipment they ultimately own; whereas landlords are held responsible for houses or buildings they own and rent to others: “The modern landlord still performs a real function in looking after the capital goods in his ownership, while most other property owners hardly do so any longer.”

The book closes with chapters on progress and inequality. The former is a discussion of the various reasons why national income does not measure progress even though it is the best single indicator possible. The latter chapter ends: “It is important that [inequality of income] should be kept in check; but it is still more important for the future of human freedom that we should not open the door to other devils in its place.” Hicks regards inequality of power as an inevitable feature of society and argues it is better to grow the national income: “Working class standards of living are much more likely to be raised by increases in production… than by changes in distribution.”

Finally, the tone of the book is fascinating. It’s a primer, and so – with the few exceptions noted above – describes the national accounts as if there are no conceptual choices to be made. This is all inevitable or a matter of pure logic. But of course the idea of national accounting was brand new and Hicks was doing a marketing job with this little book.