I just finished a book I so badly wanted to read that I almost bought two copies by mistake. It’s Sarah Bakewell’s [amazon_link id=”0701186585″ target=”_blank” ]At The Existentialist Cafe: Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails[/amazon_link].

[amazon_image id=”B017IGPTDQ” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]At The Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails[/amazon_image]

It fully lived up to my hopes. Not only had I really enjoyed her book on Montaigne, [amazon_link id=”009948515X” target=”_blank” ]How to Live[/amazon_link], but I – like Bakewell, it turns out – was a teenage existentialist. Living in a small Lancashire mill town, my plan was to be a philosopher in Paris when I grew up, hence applying to do PPE at university (and getting distracted by the E). Knowing nothing about philosophy, I turned to the library, which had a little book on existentialism, the novels of [amazon_link id=”0141198060″ target=”_blank” ]Albert Camus[/amazon_link] and Simone de Beauvour’s [amazon_link id=”009974421X” target=”_blank” ]The Second Sex[/amazon_link]. We also read [amazon_link id=”2070384411″ target=”_blank” ]Les Mains Sales[/amazon_link] in my French class at school. [amazon_link id=”009974421X” target=”_blank” ]The Second Sex in particular changed my life. [/amazon_link]

[amazon_image id=”0141198060″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Outsider (Penguin Modern Classics)[/amazon_image] [amazon_image id=”009974421X” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Second Sex (Vintage Classics)[/amazon_image]

But enough about me. [amazon_link id=”0701186585″ target=”_blank” ]At The Existentialist Cafe[/amazon_link] is as clear a book about philosophy as you could ever hope to read, despite including chunky sections on Husserl and Heidegger. It is a jolly read about the lives of the existentialists too. (Did *you* know that Sartre had written the lyrics to one of Juliet Greco’s most successful songs? Or a film script – not used because of its length – for John Huston.) And Bakewell is a marvellous writer. For example, discussing why intentionality is hard, “The mind races round like a foraging squirrel in a park.” Her command over fresh similes and metaphors makes this book a joyous read.

I still ended up liking Beauvoir and Camus best, despite Bakewell’s appreciation for Sartre. The former for her feminism, the latter because he made the calls I agree with on political matters and – I learned here – was influenced by David Hume.

Maybe existentialism is newly relevant these days. The whole ‘behavioural’ agenda is making it important to understand the rolw perception plays in knowledge. And as for the need for a guide to how to act in a world that’s forcing difficult choices on us – well, just look at the news.

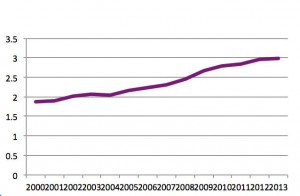

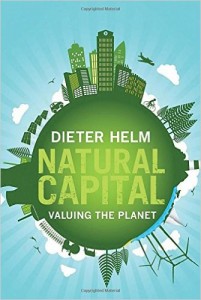

It’s a very accessible and clear explanation of why it’s important to value natural capital and how to go about it. As Dieter explains, there’s no doubt that economic growth has for some time been unsustainable. To be clear, that means that future generations (which could include our older selves) will have lower living standards because we have depleted by so much the capital stock providing economic services. (I would add infrastructure too, as part of the sustainability challenge, and there are similar issues as looking at renewable natural capital.)

It’s a very accessible and clear explanation of why it’s important to value natural capital and how to go about it. As Dieter explains, there’s no doubt that economic growth has for some time been unsustainable. To be clear, that means that future generations (which could include our older selves) will have lower living standards because we have depleted by so much the capital stock providing economic services. (I would add infrastructure too, as part of the sustainability challenge, and there are similar issues as looking at renewable natural capital.)