I bought Exact Thinking in Demented Times by Karl Sigmund for the genius title, and absolutely loved the book. The subtitle explains what it’s about: The Vienna Circle and the Epic Quest for the Foundations of Science. Karl Sigmund, the flyleaf tells me, is a maths professor at the University of Vienna and one of the pioneers of evolutionary game theory. He also co-curated an exhibition on the Vienna Circle, the inter-war group of philosophers, mathematicians and physicists who between them revolutionised the world’s understanding of – well, the world. Against idealism and metaphysics, seeking the unity of science, their logical positivism transformed Anglo-American philosophy, not least because so many of the Circle’s members had to flee Austria in the 1930s.

Who would have thought this could make a rip-roaring read? The book explains the philosophy and maths in just enough detail – there were a few bits about the maths I decided not to re-read – and weaves the ideas with the personalities, friendships and jealousies. It adds up to a wonderful intellectual history of a place and time. Jenny Uglow’s equally wonderful The Lunar Men would be a good comparator.

I’m not a big fan of logical positivism, or so I thought. Exact/Demented sent me back to my undergraduate copy of A J Ayer’s Language, Truth and Logic, which introduced the ideas to the British public (well, bits of it). I wrote the date inside, and I must have bought it enthusiastically in my first week at Oxford. Looking again reminded me how frustrating I found what seemed like meaningless quibbles about words – “easily understood by the layman”, the back cover claims. Hah! However, Exact/Demented gives a much richer account of the strands of thought in the Vienna Circle and makes it clear that the linguistic rabbit hole was but one element of the underlying empiricism. The account also completely reinforces my belief that Wittgenstein’s work is objectively meaningless and what’s more he was a complete pillock. (Although when I tweeted something from Douglas Hoftstadter’s intro to the book to the same effect, it turned out there are a few pro-Wittgenstein trolls on Twitter, so I’ll get into trouble with them again.)

Other obvious characters feature in the story, such as Kurt Godel, Rudolf Carnap and the positivism critic Karl Popper, as well as Einstein, and lesser known (to me) people, including the Circle’s leading light Moritz Schlick, and some economists orbiting around (Oskar Morgenstern, John von Neumann). The story is bookended by two murders of philosophers, and two tragic world wars. The Vienna Circle survivors ended up split between universities in the US and UK – on one occasion Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, Kurt Godel and Wolfgang Pauli all ended up socialising in Princeton, discussing time travel. What an occasion.

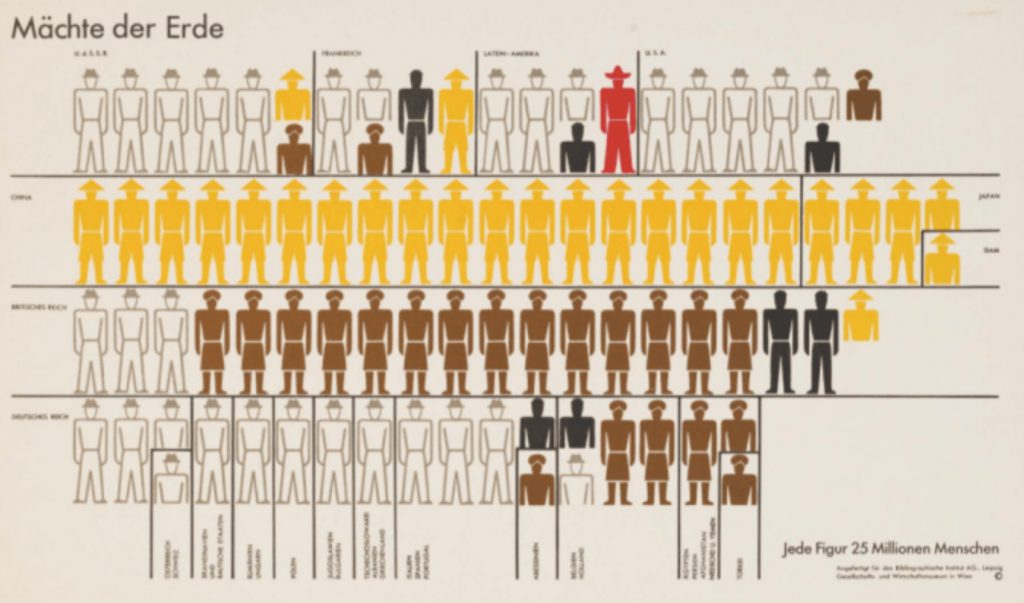

Given my own research interest at the moment, I was particularly pleased to learn about Otto Neurath’s innovative data visualization method, through his Institute for Pictorial Statistics, designed to present socio-economic statistics in a form most people could understand. The signature style was the use of rows of little human figures, which ended up being called ‘Isotype’. Who knew infographics were invented in the 1930s?

Poignantly, in 1939 Otto Neurath published a bestseller called Modern Man in the Making. “It employed a tight mesh of texts and pictures to describe the dawning world of globalized exchange, international migration and limitless progress.” How his readers must have been wishing that were true.

Poignantly, in 1939 Otto Neurath published a bestseller called Modern Man in the Making. “It employed a tight mesh of texts and pictures to describe the dawning world of globalized exchange, international migration and limitless progress.” How his readers must have been wishing that were true.

And this is the other attraction of this wonderful book. Its subtext throughout is both the need for and the threat to Exact Thinking in Demented Times, a message relevant today.

[amazon_link asins=’0465096956′ template=’ProductAd’ store=’enlighteconom-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’36b4c5e3-f931-11e7-9b5d-2fc3a9a6874f’]