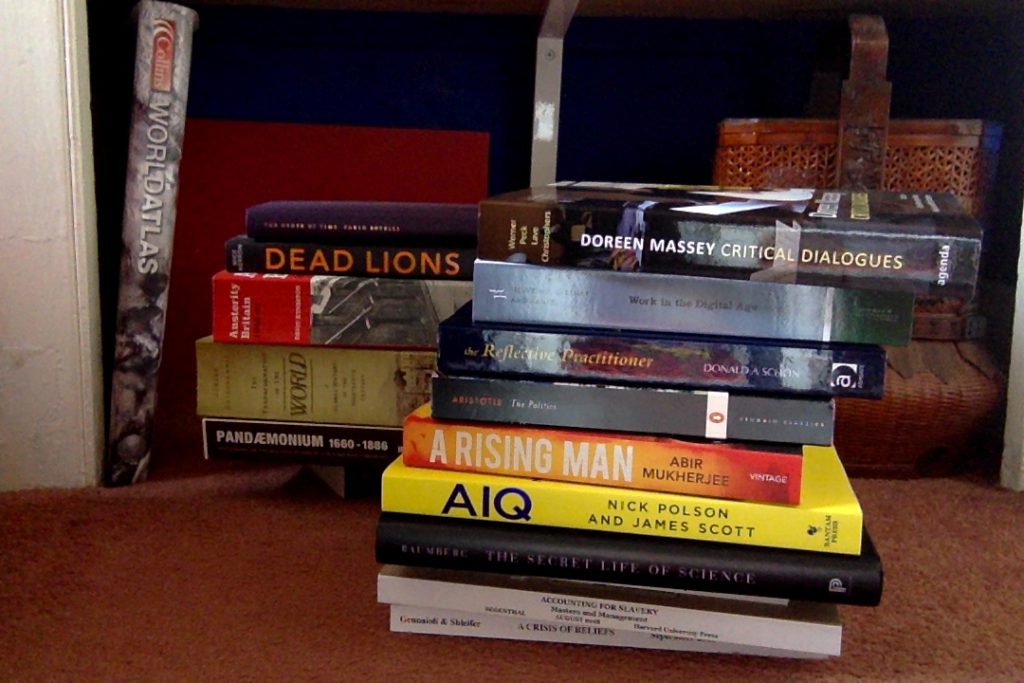

This week I’ve been dipping in to Work in the Digital Age: Challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, edited by Neufeind, O’Reilly and Ranft. This is a collection of short essays brought togoether by Policy Network, the centre-left ‘progressive’ think tank. It’s a chunky book, starting with sections essays on prospects for employment and the character of work. These cover, for example, the likely impact of automation in destroying and creating jobs, and the nature of work in the ‘gig’ economy. A section on labour relations and the welfare state follows. There are then chapters on individual European countries, ordered according to the ‘digital density’: Scandinavia and the Netherlands are classed as high, the UK and Germany medium, France, Italy and Central and Eastern Europe as low. There are also chapters on the US, Canada and India. The comparisons between countries were at the heart of the project, and I admit to not having read these chapters.

Given that I read so much of the economic literature on these issues, I haven’t found anything startlingly new so far, although there are some interesting perspectives. For example Martin Kenney and John Zysman consider the question of financing technology start-ups when they face a long period of losses because of what’s known in the platform literature as the chicken and egg problem: a platform needs users on both sides – riders as well as drivers for instance – because it won’t attract riders without enough drives and won’t have enough drivers unless it has a user base. The winner-take-all success stories then look for a long period of rents to recover those early losses, although many platforms simply fail. The essay argues that it is not clear whether this financing model is creating economic and social value. (I argue in a forthcoming paper that this is one aspect of the wider failure of competition economics to have figured out how to compare static welfare gains and losses to dynamic ones.)

In other chapters, Ursula Huws et al report new surveys on the extent of gig work or crowd work – from 9% in the UK to 22% in Italy, usually as part of a broader spectrum of casual work; Monique Kremer and Robert Went set out an agenda for ensuring automation does not increase inequality, covering the direction of robotisation, the enhancement of complementary skills, and distributional policy instruments; and in an introductory essay Luc Soete on the productivity paradox discusses similarities with and differences from previous technological revolutions. The final chapter sets out a reform agenda – education and training; work transitions; social protection; redistributive taxes and transfers; and investing in infrastructure and innovation. This is high level stuff, and therefore a bit motherhood and apple pie. Having contributed essays to this kind of collection myself, I know this pitch of generality is inevitable, but do ache for some policy specifics as opposed to ‘a new inclusive narrative’.

For an overview of the technology and work debate, this is a useful volume, though, and it can be downloaded free from here. It’s certainly a good place to start for a comparative perspective, and the references to country-specific literature look really useful.

[amazon_link asins=’B07D5ZZD77′ template=’ProductAd’ store=’enlighteconom-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’35442710-9322-11e8-93ed-f1b496423b7d’]