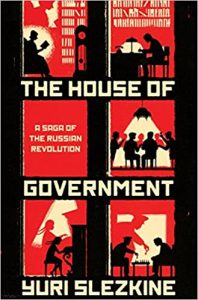

Well. It’s been a slow blogging start to March because I’ve been reading Yuri Slezkine’s 1000-page The House of Government. What an amazing book.

It’s an account of the Russian Revolution and the early years of Lenin and Stalin up to the second world war. The book is unlike anything I’ve read before, and is utterly compelling. It braids together an argument presenting early-Soviet Bolshevism as a millenarian religious sect, the sequence of events that led up to the Terror to a large degree as reflected in literature and literary debates, and the perspective of the families who lived in the House of Government, the huge mansion blocks opposite the Kremlin that housed the nomenklatura. The extent of the sources on which the book is based is simply staggering, from archival records to newspapers to personal letters and photographs, and evidently also many conversations with people who had been children at the time. The fact that throughout many hundreds of pages we have met and seen the wives and children makes the final section – parents arrested in the night and never seen again, young children sent to orphanages after their early years of privilege – incredibly affecting.

The device of using the building as the lens on history is what makes the personal thread so effective, but clearly also means this is – despite its length – an incomplete account of early Soviet history. Indeed, it assumes a lot of background knowledge, which I could more or less dredge up from 1st year comparative politics. Nor do I know what I think about Bolshevism as a sect of true believers: it seems plausible in some ways, but again is unlikely to be the whole story. At least, other forms of Marxism are available.

But you shouldn’t approach The House of Government as you would an ordinary history book, even though the people are real, and their words from letters and diaries are quoted at length. It’s obviously a very personal interpretation. I did end up thinking that along with Svetlana Alexeivich’s Second Hand Time, this book opened an emotional window on the USSR that help understand it current-day Russia: traumatic historical events cast a long shadow. Get ready to read an epic. And to read it with a table or pillow to prop it on.