My journey back yesterday from the Royal Economic Society annual conference in Manchester was delayed for ages because some poor soul had thrown themselves under a train along the line. At least I managed to finish [amazon_link id=”0674725654″ target=”_blank” ]The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism[/amazon_link] by David Kotz.

[amazon_image id=”B00SR5FNSY” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism[/amazon_image]

I’m a bit allergic to the word ‘neoliberal’, probably because it’s so often used as generic and blanket abuse of (among other things) all of economics. I’ve been accused of neoliberalism myself (to which the only sensible response is that the accuser needs to get out more if they think I’m an ideologue…..)

Certainly Kotz signals his own ideological views by using the term as his descriptor of American capitalism, but he does have a far more precise and meaningful definition than is the norm. He defines it as a specific “social structure of accumulation”, a “particular configuration of economic and political institutions, as well as dominant economic theories and ideas.” This is interesting, and I buy the general approach – it’s similar to (for example) Michael Best’s use of the concept of “production systems” in [amazon_link id=”0198297459″ target=”_blank” ]The New Competitive Advantage[/amazon_link], but ranging wider beyond the economic institutions of production.

Kotz sees the 1950s and 60s as a golden age of ‘regulated capitalism’ with strong unions and well-paid jobs for (male) breadwinners. He accepts that it had its own crisis, with sustained declines in profitability through the 1970s. Hence the scope for the arrival of ‘neoliberal capitalism’ from 1979/81 with Thatcher and Reagan.

Much of the book describes the development of the ‘neoliberal’ system after that turning point in terms of the broad outlines of the US economy – profit rates and shares, declining union membership, stagnant median real wages, the rise in household indebtedness etc. It does not cover globalisation to any great extent, which seems an important omission, nor does it mention technology or environmental sustainability at all, so the prism is quite narrow. Deindustrialisation is described more in terms of an attack on organised labour than the consequence of several deeper economic trends. However, the book’s analysis of the 2008 crisis in terms of the preceding financial bubble, and the way consumption was supported by debt, is surely not controversial.

Kotz does mention the role of ideas in economic theory and – more important in the long term – political received wisdom (the theory has moved on, but the policy world view far less so). He describes neoliberal ideology as “very strong” – clear, simple, apparently logical. Daniel Stedman-Jones’s [amazon_link id=”B00RWOZWD2″ target=”_blank” ]Masters of the Universe[/amazon_link] gives a much fuller account of the effort it took to cement the ideology over a number of decades prior to 1979, and highlights how much organisation it will take to change the prevailing world view. For I think this is a question of political and social organisation more than one of economic or political theorising.

Kotz argues here that the US and by extension the western economic system is in a state of crisis that will give way to a new “social structure of accumulation” whose shape is yet to be determined – it could be a revived neoliberal system. It will not be his preferred socialist system without a broad social movement, as at moments of crisis in the past such as 1945.

I would agree with Kotz that the prevailing production system or social structure is in crisis, but would emphasise more the fundamental role of technology and globalization. Not that a class-based perspective isn’t important. He concludes: “The path that will be followed in the years ahead cannot be predicted …. The economic changes – or lack of changes – that lie ahead will be the outcome of struggles among various groups and classes in the coming years, which will occur in the realm of ideas, politics and culture.” And surely the realm of the work place, public space and policy corridors too?

So all in all, I agreed with quite a lot of the analysis here while thinking it an incomplete picture. Still, the book irked me, no doubt because of my allergy to ‘neoliberalism’, along with its slightly plodding style. Reading it did feel a bit like being in a political meeting where you are washed over by a wave of abstract nouns. I know economists are on average pretty clunky writers so one should be used to it, but I did nod off over the book as my train trundled veeeery slowly through the countryside.

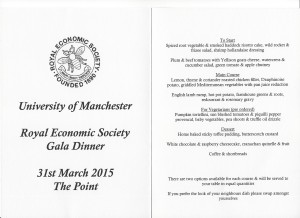

I wonder what Professor Kotz would have thought of the arrangement at dinner at the Royal Economic Society conference. There were two options for each course, and staff served each one to alternating places at the table. If you preferred the other, you had to exchange. Perfectly efficient and logical – surely only an economist could have thought of it? I’m tempted to do this every time I invite people round for a meal in future, unless that would be a bit neoliberal.

Instructions at the bottom – side payments not ruled out.