Ha-Joon Chang’s Edible Economics: The World in 17 Dishes is an entertaining read, and a nice introduction to some economic questions. Regular readers of his will not be surprised by the economic analysis – heavy on infant industry protection as the path to development for low income countries. But I did very much enjoy the food links – each chapter is an ingredient (rather than a dish), garlic, anchovy, strawberry and so on. There were nice nuggets from food history – the corporate history of Oxo and corned beef for instance, or that Koreans used to snack on fried silkworm pupae as a cheap source of protein as it was a byproduct of the silk export industry.

On the economics, the world has moved significantly towards Ha-Joon’s emphasis on active industrial policy, so he can feel vindicated in that respect. He also acknowledges here that it can go wrong, which I hadn’t spotted stated so clearly in his previous books. I’m not sure his perception of the economics profession as a monoculture with a few brave heterodox souls, set out again in the intro here, is as correct as it used to be; my perception is that it is broadening considerably and has been for a while, certainly outside the US.

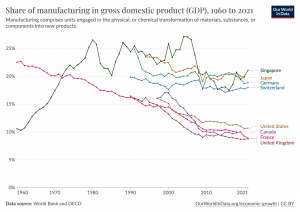

The fact in the book that really surprised me is its claim that Switzerland and Singapore are the most manufacturing-intensive economies in the world – the World Bank data suggest this is a bit of an overstatement but they do have higher manufacturing sectors relative to GDP than one might imagine and are in the Germany?Japan clud (Our World in Data figure below.) As my colleague Jostein Hauge – cited here – has written about in his book The Future of the Factory, the economy no longer divides cleanly into manufacturing vs services, as many high value services serve the manufacturing sector. I think we’d do well to get away from that as a key distinction but do believe – as Ha-Joon doesn’t seem to – that there has been an important shift in the structure of the advanced economies. Manufacturing is central as it’s one of the highest value activities, but the way in which it is central has changed.

Anyway, it’s a good debate and the book is a good read, super-accessible for non-economists. I prefer it to some of his earlier popular books because there are far fewer sideswipes at other economists, and I learned a lot about the history and culture of some of the selected foods too. All that’s missing are recipes.