With Eurostar journeys coming up, I anticipate making decent inroads into Piketty’s [amazon_link id=”067443000X” target=”_blank” ]Capital[/amazon_link], but meanwhile the enormous buzz about it makes it harder than ever to understand why the popular and intellectual anger about plutocracy has not translated (yet?) into political consequences.

This thought was underlined by browsing through [amazon_link id=”0691155240″ target=”_blank” ]Fragile By Design: The Political Origins of Banking Crises and Scarce Credit[/amazon_link] by Charles Calomiris and Stephen Haber. They write: “There is no avoiding the government-banker partnership.” The book combines history, economics and political science to analyse the nature of the state-bank relationship, within a framework of bargaining. One section compares and contrasts the US (12 systemic banking crises since 1840) and Canada (zero). Another looks at the relationship in authoritarian contexts and democratic transitions.

[amazon_image id=”0691155240″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Fragile by Design: The Political Origins of Banking Crises and Scarce Credit (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)[/amazon_image]

One important conclusion is that no general theory can explain why banking crises have not been equally likely in all countries in the recent past. For example, [amazon_link id=”0071592997″ target=”_blank” ]Hyman Minsky[/amazon_link]’s theory of endogenous excess followed by fear has enjoyed a revival – indeed there was a recent BBC Radio 4 Analysis on it (Why Minsky Matters) that is well worth a listen – but why was Canada exempt from these oscillations arising from human nature? It isn’t that Minsky is wrong, but rather that context matters for crises too. “Useful propositions about banking generally are only true contingently, depending on historical context.” And, to mangle [amazon_link id=”0140449175″ target=”_blank” ]Tolstoy[/amazon_link], every country (except Canada?) has its own unhappy politics.

Which brings me back to the strange absence of any political consequence of the financial crisis for banking. Bankers will complain about excess regulation but the only result has been to cause them to employ more compliance officers, and more lawyers to game the regulations. There has been little action on leverage and capital ratios, next to none on scandalous rent-seeking bonuses and none at all enforcing competition and new entry. The financial sector isn’t the only locus of the modern plutocracy, but it is one of the most significant.

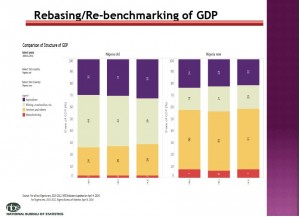

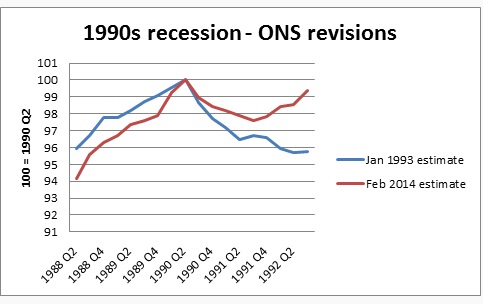

One possibility is that the political classes are befuddled because – as I describe in [amazon_link id=”0691156794″ target=”_blank” ]GDP: A Brief But Affectionate History[/amazon_link] – the national accounts figures overstate the contribution of the financial sector to the economy. Maybe some politicians genuinely believe they cannot risk killing the goose that’s laying the golden eggs even if it is keeping all the eggs within its own nest. Whatever the explanation, the bargain between banks and politics is working for bankers, and not for other citizens.

Here is an excellent VoxEU interview about the book with Charles Calomiris. For now, I’m off to St Pancras and on with Piketty.

[amazon_image id=”067443000X” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Capital in the Twenty-First Century[/amazon_image]