I finished reading Sven Beckert’s prize-winning [amazon_link id=”0141979984″ target=”_blank” ]Empire of Cotton: A new history of global capitalism[/amazon_link] in Cottonopolis, aka Manchester. I grew up in Lancashire in a family many of whose members worked in the cotton mills. The noise and hot greasy, dusty smell of the mills was part of my childhood. At school we were taught that we had been the cradle of the Industrial Revolution: John Kay, Richard Arkwright, Samuel Crompton, created their inventions just down the road. In Lincoln Square in Manchester stands a statue of Abraham Lincoln, a recognition of the support Lancashire mill workers had given to the Union side in the American Civil War, even though the blockade of southern ports created the ‘cotton famine’ that was the source of the great hardship they were experiencing.

[amazon_image id=”0141979984″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Empire of Cotton: A New History of Global Capitalism[/amazon_image]

Not surprisingly, I’ve been immensely looking forward to reading [amazon_link id=”0141979984″ target=”_blank” ]Empire of Cotton[/amazon_link], saving it as a treat. And although I enjoyed reading it, it also left me very uneasy. The book wraps a huge amount of fascinating detail and insight around a single unwavering theme: that ‘war capitalism’, the violence of empire and slavery and thus the creation of a global trade with protected markets, made possible industrial capitalism. Now, I’m no imperialist, and there’s no question about the horrors of the slave trade – and the riches it created in the UK. David Olusoga’s recent BBC TV series about the UCL project on the legacy of British slave ownership highlighted the foundational importance of slavery for the UK’s 19th century prosperity, despite abolition. Even so, I distrusted the book. In 441 pages of great detail, was there really no room to mention those Lancashire mill hands? It isn’t an unknown story: Radio 4’s In Our Time had a fabulous episode on it earlier this year. Yet the book’s chapter on the cotton famine speaks only of ‘Manchester’ as a solo voice and its concern about the Union blockade. Life – and history – are more complicated than a [amazon_link id=”0415304458″ target=”_blank” ]Rosa Luxemburg[/amazon_link]-like frame with no room for anything that clouds the simplicity of an argument.

But this is – well, more than a quibble, just not enough to have stopped me enjoying the book. Three points were particularly interesting.

First was the analysis of the interaction between the labour-intensive upstream production and the capital-intensive downstream production, and how the technological practicalities shaped the organisation of processing, manufacture and trade. Although cotton is probably now the lowest profile industry of the industrial revolution, [amazon_link id=”B00PYY1AQU” target=”_blank” ]Empire of Cotton [/amazon_link]makes a persuasive case that it was the most powerful driver of globalised industrial capitalism – global precisely because of the differing production technologies along the supply chain.

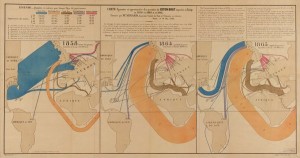

Second is the emphasis on the interaction between private interests and the state, and the prevalence of the same kind of argument we still hear from industrialists who talk about the importance of free trade and yet constantly lobby the government to shape taxation, infrastructure, trade rules etc in their interests. The American Civil War prompted much British investment in Indian infrastructure, for example, as cotton manufacturers successfully lobbied for government assistance to create new sources of their raw material. More generally, the book quite rightly underlines the joint innovation of technologies, the organisation of production and trade, and financial and social institutional innovations.

Minard’s infographic on the flows of raw cotton imports showing the effect of the Civil War

Third – and this is a truly nerdy point – I found fascinating the role of standardisation (of types and qualities of cotton) as the trade grew. In the early stages of the rise of cotton, the gathering of detailed information was a source of competitive advantage. Over time, places that collected information, and then provided it in standardised form, became central to the business. Liverpool was the centre of both physical and informational trade in the UK; in the US, although the South grew the cotton, New York became the hub. Ultimately, US standards dominated: in 1923 the Cotton Standards Act made it illegal to use anything but American standards in interstate or foreign commerce, so they became global standards. “The state also became an important supplier of statistics that made the market more legible, rendering much less central the sophisticated networks of information gathering and exchange that merchants had forged…. The state, centrally concerned with the reliable flow of inexpensive raw materials into the vortex of manufacturing enterprises, now quite literally made the market.”

So, I agree with some of Beckert’s argument and do recommend reading [amazon_link id=”0141979984″ target=”_blank” ]Empire of Cotton,[/amazon_link] – but with a large pinch of scepticism.

Joseph Coyle (far right, front, aged 14 with his workmates at the Old Ground Mill in Ramsbottom, Lancashire.