Yesterday on my travels I read a short book, [amazon_link id=”0300209584″ target=”_blank” ]Income Inequality: why it matters and why most economists didn’t notice[/amazon_link], by Matthew Drennan. Professor Drennan is an urban planning expert, so having read the book’s blurb, I expected it to be a critique of the economics profession, and braced myself.

[amazon_image id=”0300209584″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Income Inequality: Why it Matters and Why Most Economists Didn’t Notice[/amazon_image]

It ended up not being what I expected. In fact, the book repeats Raghuram Rajan’s argument in [amazon_link id=”0691152632″ target=”_blank” ]Fault Lines[/amazon_link] – that low-income Americans went into debt to increase their consumption levels as well as buy homes, keeping up somewhat with the rich thanks to easy credit. One of the central chapters has a long appendix reporting some econometric work claiming to establish causality between higher income inequality and higher debt. However, it is not sufficiently detailed to be able to assess the empirical work, while too technical to be of interest to the general reader. So the central section of the book is a bit odd.

It’s a fair cop to say the generality of the economics profession did not pay enough attention to rising income inequality. The biggest lasting impact of Piketty’s [amazon_link id=”067443000X” target=”_blank” ]Capital in the 21st Century[/amazon_link], and the work with Atkinson and Saez on which it was based, will turn out to have been consciousness raising. Nobody is ignoring it now. However, there are now several important books on this subject: as well as [amazon_link id=”0691152632″ target=”_blank” ]Faultlines[/amazon_link] and [amazon_link id=”067443000X” target=”_blank” ]Capital in the 21st Century[/amazon_link], Mian and Sufi’s [amazon_link id=”022608194X” target=”_blank” ]House of Debt[/amazon_link], Atkinson’s [amazon_link id=”0674504763″ target=”_blank” ]Inequality[/amazon_link], Francois Bourguignon’s [amazon_link id=”069116052X” target=”_blank” ]The Globalization of Inequality[/amazon_link] and Branko Milanovic’s forthcoming [amazon_link id=”067473713X” target=”_blank” ]Global Inequality: a new approach for the age of globalisation[/amazon_link]. I didn’t find much novelty in Drennan’s [amazon_link id=”B017DNAI3A” target=”_blank” ]Income Inequality[/amazon_link], although it is at least a short introduction.

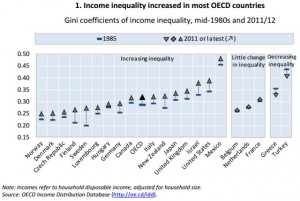

Above all, though, my reaction to the book wasn’t that it was about economics, more that it was about America. We do tend to forget that inequality is greater in the US than most other OECD countries, and has risen more. Perhaps it can act as the canary in the cage for the rest of us, but a good part of the story lies in US politics and institutions. After all, just look at the Republican primary contenders.

OECD income inequality