When I was growing up in a Lancashire mill town in the 1960s and 70s, every Friday evening we went to the fish and chip shop to buy our meal. The particular delicacy was an upside-down pea mixture: mushy peas on top of the chips, which were then soaked through and green. But this post isn’t about British culinary delicacies, but rather about what the transaction included. Because it was the practice to take your plates and dishes to the shop, where the food was placed on them and wrapped in newspaper. You were buying fish, chips, peas and some paper. This is a contrast to today’s practice of buying in addition a polystyrene tray, and a contrast to buying a meal in a restaurant, or beer in a pub, where you are buying the food and renting the plate or glass.

These reflections about the nature of the property being exchanged in a market transaction came about because I read an article in the Financial Times about a plan for a second hand market for digital goods in Europe, to be launched by ReDigi, which is running one in the US already. It sells for 60 cents songs already bought online for 99 cents. Needless to say, the company has been taken to court in the US) by Capitol Records), for breaching ‘intellectual property’ rights.This is entirely in line with the instinct of the “content owning” industry – witness the way games companies have tried to restrict the second hand market in physical games by adding one-time only codes, and requiring purchasers of pre-owned games to also buy a new code to unlock the game.

The outcome of the ReDigi case will be fascinating: the question is whether something that is ‘property’ in the initial transaction ceases to be property for the purposes of a secondary transaction. Ultimately, it might be the case that digital purchases of books and music become more explicitly a rental model, as the capacity and claimed willingness of vendors such as Amazon to delete purchased e-books or enforce restrictive DRM already hints. Digital goods are a special case because there is no degradation of the second-hand compared to the new item. There are none of the information asymmetry ‘market for lemons’ problems arising from the unknown quality of a physical good such as a car (although not a physical book or garment, which can be inspected in the charity store).

Browsing around about this subject, I’m surprised to find how little research on second hand markets is available. The few journal articles I found – mostly dating back to the 1990s or early 2000s – suggest that second hand markets can increase rather than decrease the size of new goods markets, because consumers will upgrade more often if they can recoup some of their earlier purchase from selling them second hand. What’s more, it would be incorrect to assume anyway that used goods cannibalise new sales, because at least some consumers would never buy them at the higher, new prices. (Cory Doctorow picked up this point in the context of e-books in a 2005 piece.) And of course, we apply different standards, and different concepts of property, in different markets. There is the digital/physical divide, but also the divide between, for example, books, first edition or antiquarian books, and art – rarity determines not only whether second hand cheaper or more expensive, but also our cultural attitudes to buying in the used-goods market.

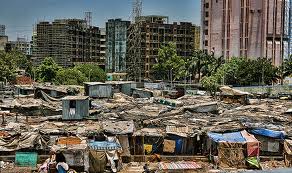

In the real world, second hand is huge. It’s huge in developed markets – see, for example, this Guardian article about the post-Christmas surge for charity shops – especially during a recession. It’s bigger still in developing country markets, where clothes and other goods such as mobile phones from the richer countries are sold on a large scale in the markets. This may be one of the all-too-frequent examples of a subject not being studied by economists because there’s no readily-available online data set on the OECD or World Bank websites. The one book I managed to find on contemporary society on Amazon is a 2003 anthropological study of [amazon_link id=”1859736726″ target=”_blank” ]Second Hand Cultures[/amazon_link]. (There is also [amazon_link id=”0230229468″ target=”_blank” ]Modernity and Second Hand Trade: European Consumption Cultures and Practices 1700-1900[/amazon_link].)

[amazon_image id=”1859736726″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Second-hand Cultures (Materializing Culture)[/amazon_image]

If anybody knows of relevant books in any social science discipline, I’d love to know. This subject is a dog that hasn’t barked, but maybe that will change.