The best museum I’ve ever visited is the Stasi museum in Berlin. Mainly text and photos, it gives a compelling image of life under surveillance socialism. It even had its own technologies, from the steam iron (to steam open letters), to the pinhole cameras and disguises for agents in the field, to the unique rotating filing systems and square punch cards to record the masses of information. (And how the ratio of information to physical mass – although not energy use – has changed over the decades. Nordhaus’s well-known paper on the cost of computation tries to measure a related phenomenon.)

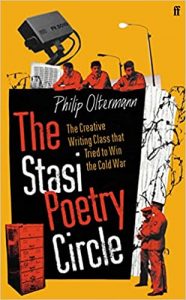

All this by way of prelude to recommending The Stasi Poetry Circle by Philip Oltermann. Although vaguely aware of the cultural dimension to the Cold War, it was still striking to learn that the East German regime had a poetry initiative among its elite Stasi regiment to try to win hearts and minds. It’s a marvellous book.

One nugget I particularly enjoyed was this: “Publishers, like their customers, had to adhere to the principles of a planned economy: in terms of books printed, the stated aim was a yearly increase in productivity of four to five percent. Between 1950 and 1989 both the number of books printed and the proportion of those that were fiction more than tripled.” It seems to have had some payoff: one international survey in the late 1980s found that East Germans had a higher reading comprehension age than their West German counterparts. This is the kind of productivity initiative I can get behind.

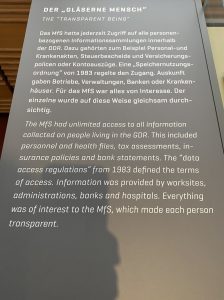

Another anecdote that leapt out: one Stasi guard to one of the poets who refused to join the Party’s youth wing on the grounds of preferring his own interior world: “If you are a decent human being, then there’s no world inside you other than the world you can see from the outside.” The concept was the gläserne mensch, transparent person.