It’s International Women’s Day and my Sunday newspaper has a big feature asking ‘Does Tech Have a Women problem?’ (bizarrely, for a tech supplement, not online). A question to which the answer is ‘Duh!’ Shockingly (for a social science), economics isn’t any better. Noah Smith forcefully pointed this out in a recent column. In the UK, the Royal Economic Society is soon due to publish another report on the proportion of women at different levels in the academic hierarchy, but there’s no reason to think it will be better than the 2012 outcomes. My university is celebrating its women with a little film (including me, hmm) but I don’t think my department is any better than the norm for economics.

There’s no quick fix; it will take a mixture of encouraging female role models for young women economists and students (especially while still at school), making sure all-male panels don’t feature at conferences, raising the consciousness of hiring and promotion panels so they do not confuse “best candidate” with “male”, and so on.

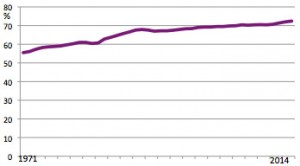

Start today by reading some relevant economics books! I just read Katrine Marçal’s [amazon_link id=”1846275644″ target=”_blank” ]Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner?[/amazon_link] (I’m reviewing it elsewhere) and although irritating in some if its generalizations about economics, it’s terrific about the role of women in the economy and economics, and is a short and enjoyable read. One of its central arguments is about the need to measure better (mainly) women’s unpaid work outside the market, not included in GDP, something also advocated in my [amazon_link id=”0691156794″ target=”_blank” ]GDP[/amazon_link]. As the chart below shows, the increase in the UK’s female economic activity rate during the past generation has been substantial (up from 55.5% to 72.4%) and it is extraordinary not to have regular data that make it possible to evaluate the consequences of switching between unpaid and marketed work.

Jonathan Gershuny and his team gather time-use data to explore who does what in the non-market economy in the UK – a new survey is due to be published early in 2016. The database on their website has a bibliography of relevant publications covering time use data from around the world.

[amazon_image id=”B00TOLYFOS” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner?: A Story About Women and Economics[/amazon_image] [amazon_image id=”1861342004″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Seven Years in the Lives of British Families: Evidence on the Dynamics of Social Change from the British Household Panel Survey[/amazon_image] [amazon_image id=”B00MXDLPSI” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History by Coyle, Diane (2014) Hardcover[/amazon_image]

Recently I reviewed here [amazon_link id=”B00KAJJBYM” target=”_blank” ]Why Gender Matters in Economics[/amazon_link] by Mukesh Eswaran. Women younger than me are unlikely to have read Simone De Beauvoir’s [amazon_link id=”009974421X” target=”_blank” ]The Second Sex[/amazon_link] – it was all the rage among 1970s/80s vintage feminists. It’s a book that changed my life. Although far more about culture than about economics, it places huge emphasis on the vital need for economic autonomy for women. There is of course a Journal of Feminist Economics. Amartya Sen’s eye-opening article about missing women is 15 years old now. Nothing has changed. The attitudes in India to rape are shocking evidence of that.

[amazon_image id=”B00QASWUU4″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ][(Why Gender Matters in Economics)] [ By (author) Mukesh Eswaran ] [September, 2014][/amazon_image] [amazon_image id=”0140034633″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Second Sex (Penguin Modern Classics)[/amazon_image]

It would be great to gather more reading suggestions – welcome in comments or via Twitter.